Piano tuning by Weiner Piano Service

Guest artist accommodations: Hal and Debbie Lurtsema

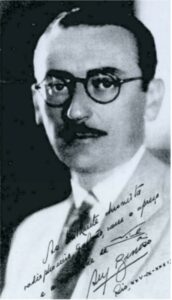

Ary Barroso spent much of his career in Rio de Janeiro, first as a pianist for dance bands and movies, then as a composer for musical theater. He also worked as a radio and television programmer, and he wrote the music for Walt Disney’s The Three Caballeros in 1944. One of the most important composers of the urban samba in the 1930s, Barroso composed more than 160, of which his most famous is Aquarela do Brasil (Watercolor of Brazil). He said he wrote this samba one night in early 1939 when a heavy rainstorm kept him housebound. Its name was shortened to Brazil when it was recorded in the United States.

Ary Barroso spent much of his career in Rio de Janeiro, first as a pianist for dance bands and movies, then as a composer for musical theater. He also worked as a radio and television programmer, and he wrote the music for Walt Disney’s The Three Caballeros in 1944. One of the most important composers of the urban samba in the 1930s, Barroso composed more than 160, of which his most famous is Aquarela do Brasil (Watercolor of Brazil). He said he wrote this samba one night in early 1939 when a heavy rainstorm kept him housebound. Its name was shortened to Brazil when it was recorded in the United States.

A typical samba features not only engaging instrumental dance music but a soloist singing verses in alternation with a chorus singing the refrain. Barroso’s text for Brazil praised the country in highly patriotic terms, which created a new samba genre, the samba-exaltação (exaltation samba). The song has become almost a Brazilian national anthem owing to its text and catchy music, though it was not an instant hit. Aquarela do Brasil received several live performances and recordings in Brazil in 1939, but it took Walt Disney’s 1942 animated film Saludos amigos to launch its stardom both in Brazil and around the world. Brazil has since been arranged in countless versions, many of them purely instrumental, such as the present orchestral version by John Wasson.

—© Jane Vial Jaffe

Scored for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, clarinets. 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, shaker, claves, cowbell, xylophone, harp, and strings

American composer and conductor of Chinese birth, Tan Dun strives to break the boundaries between the classical and nonclassical, East and West, and avant-garde and indigenous art forms as he reaches out to new and diverse audiences. Known to millions for his Academy Award–winning score for the film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, he has also received such prestigious honors as the Grammy, Grawemeyer, and Shostakovich Awards; the Bach Prize; and, for lifetime achievement, both Italy’s Golden Lion Award and the Istanbul Music Festival’s Award. Tan Dun’s music has been played throughout the world and on radio and television by leading orchestras, opera houses, and international festivals, and since 2019 he has served as dean of the Bard College Conservatory of Music.

American composer and conductor of Chinese birth, Tan Dun strives to break the boundaries between the classical and nonclassical, East and West, and avant-garde and indigenous art forms as he reaches out to new and diverse audiences. Known to millions for his Academy Award–winning score for the film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, he has also received such prestigious honors as the Grammy, Grawemeyer, and Shostakovich Awards; the Bach Prize; and, for lifetime achievement, both Italy’s Golden Lion Award and the Istanbul Music Festival’s Award. Tan Dun’s music has been played throughout the world and on radio and television by leading orchestras, opera houses, and international festivals, and since 2019 he has served as dean of the Bard College Conservatory of Music.

Tan Dun also conducts groundbreaking works with leading orchestras worldwide, among them the London Philharmonic Orchestra, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra, Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, Orchestre National de France, BBC Symphony Orchestra, and Filarmonica della Scala. An artistic ambassador of Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, he also serves as honorary artistic director and/or chief guest conductor of the China National Symphony, the Shenzhen Symphony, and the Xi´an Symphony Orchestra.

Tan Dun discovered twentieth-century Western classical music with his fellow students at the newly reopened Central Conservatory in Beijing once the restrictions of the Cultural Revolution had been lifted. Leading the “New Wave” composers of contemporary music, he embraced the new cultural pluralism in the arts and found himself the center of political controversy. He moved to New York in 1986 to study at Columbia University with Chou Wen-chung and Mario Davidovsky, earning his doctorate in 1993.

Several distinct series reflect Tan Dun’s interest in combining classical music traditions with outside influences. The Orchestral Theater series infuses his memories of shamanistic rituals into symphonic performances and is represented by The Gate, premiered by Japan’s NHK Symphony. His Organic Music series, incorporating elements from the natural world, includes the Water Concerto, premiered by the New York Philharmonic, and the Paper Concerto, written for the Los Angeles Philharmonic. A third series—Multimedia and Orchestra—features The Map, a concerto for cello, video, and orchestra premiered by Yo-Yo Ma and the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Most recently, Tan Dun led the premiere of his epic 2018 oratorio the Buddha Passion with the Münchner Philharmoniker at the Dresden Festival. He also conducted the work with co-commissioners the New York and Los Angeles Philharmonics and the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, as well as performances through the summer of 2023 in Hong Kong, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Amsterdam.

Tan Dun was commissioned in 2015 by Carnegie Hall to write a new piece for the National Youth Orchestra of the USA’s tour of China, which the group premiered under Charles Dutoit at Purchase College on July 10 that year, followed by the Carnegie Hall performance the following day and tour performances in China through July 26. The work, Passacaglia: Secret of Wind and Birds, combines not only East/West and ancient/modern attributes but brings together Tan’s nature and multimedia explorations by incorporating recordings of bird songs on Chinese traditional instruments played back on orchestra musicians’ and audience members’ smartphones.

The composer writes: “What is the secret of nature? Maybe only the wind and birds know. . . .

“When Carnegie Hall and the National Youth Orchestra of the United States of America asked me to write a new piece, I immediately thought to create and share the wonder of nature and a dream of the future.

“In the beginning, when human beings were first inventing music, we always looked for a way to talk to nature, to communicate with the birds and wind. Looking at ancient examples of Chinese music, there are so many compositions that imitate the sounds of nature and, specifically, birds. With this in mind, I decided to start by using six ancient Chinese instruments, the guzheng, suona, erhu, pipa, dizi, and sheng, to record bird sounds that I had composed. I formatted the recording to be playable on cellphones, turning the devices into instruments and creating a poetic forest of digital birds. The symphony orchestra is frequently expanding with the inclusion of new instruments; I thought the cellphone, carrying my digital bird sounds, might be a wonderful new instrument reflecting our life and spirit today.

“It has always been a burning passion of mine to decode the countless patterns of the sounds and colors found in nature. Leonardo da Vinci once said, ‘In order to arrive at knowledge of the motions of birds in the air, it is first necessary to acquire knowledge of the winds, which we will prove by the motions of water.’ I immediately decided to take this idea of waves and water as a mirror to discover the motions of the wind and birds. In fact, the way birds fly, the way the wind blows, the way waves ripple . . . everything in nature has already provided me with answers. With melody, rhythm, and color, I structured the sounds in a passacaglia.

“A passacaglia is, to me, made of complex variations and hidden repetitions. In this piece, I play with structure, color, harmony, melody, and texture through orchestration in eight-bar patterns. Thus, the piece begins with the sounds of ancient Chinese instruments played on cellphones, creating a chorus of digital birds and moving tradition into the future.

“Through nine evolving repetitions of the eight-bar patterns, the piece builds to a climax that is suddenly interrupted by the orchestra members chanting. This chanting reflects ancient myth and the beauty of nature. As it builds, it weaves finger snapping, whistling, and foot stamping into a powerful orchestral hip-hop energy. By the end, the winds, strings, brass, and percussion together cry out as one giant bird. To me, this last sound is that of the Phoenix, the dream of a future world.”

—©Jane Vial Jaffe; Tan Dun

Scored for 3 flutes, 3r doubling piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 xlarinets, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, drum set, tam-tam, marimba, vibraphone, flexatone, kick drum, 4 stones, 2 bird whistles, “water-whistler,” portable wireless speaker or CD player

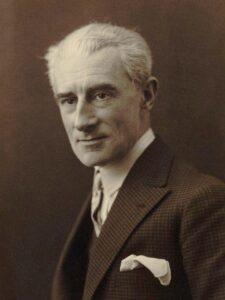

In 1928 Maurice Ravel had just successfully toured the United States and had witnessed the great success of Bolero, perhaps his most popular composition. He was contemplating an opera about Jeanne d’Arc and also wanted to compose a piano concerto, which he himself would play all over the world. While working on this concerto he received an unusual commission for a piano concerto for the left hand from Paul Wittgenstein, the Austrian pianist who had lost his right arm in the war. Ravel decided to work on both compositions simultaneously, completing them in 1931. In contrast to the seriousness of the Left-Hand Concerto, the G Major Concerto projects a buoyant, carefree atmosphere. The composer wrote:

In 1928 Maurice Ravel had just successfully toured the United States and had witnessed the great success of Bolero, perhaps his most popular composition. He was contemplating an opera about Jeanne d’Arc and also wanted to compose a piano concerto, which he himself would play all over the world. While working on this concerto he received an unusual commission for a piano concerto for the left hand from Paul Wittgenstein, the Austrian pianist who had lost his right arm in the war. Ravel decided to work on both compositions simultaneously, completing them in 1931. In contrast to the seriousness of the Left-Hand Concerto, the G Major Concerto projects a buoyant, carefree atmosphere. The composer wrote:

Planning the two piano concertos simultaneously was an interesting experience. The one in which I shall appear as the interpreter is a concerto in the truest sense of the word: I mean that it is written very much in the same spirit as those of Mozart and Saint-Saëns. The music of a concerto should, in my opinion, be lighthearted and brilliant, and not aim at profundity or dramatic effects. . . . I had intended to entitle this concerto “Divertissement.” Then it occurred to me that there was no need to do so, because the very title “Concerto” should be sufficiently clear. In some ways my Concerto is not unlike my Violin Sonata; it uses certain effects borrowed from jazz, but only in moderation.

Owing to his declining health, Ravel asked Marguerite Long to premiere the G Major Concerto, which he said would “end with trills and in pianissimo.” The completed Concerto, however, boasted a very different ending—brilliant broken chords and in fortissimo. The first performance, given on January 14, 1932, by Long with Ravel conducting, achieved great success, whereupon they took it on an extended tour. The Concerto was enthusiastically received everywhere they went, with audiences often demanding a repeat of the finale.

One of the many musicians Ravel had met in New York was George Gershwin, whose originality he praised and whose Rhapsody in Blue he greatly admired. Ravel’s “jazz effects,” no doubt influenced by Gershwin, include the use of jazz-band percussion instruments, prominent trumpet and wind parts that rival the piano part in virtuosity, rhythmic syncopations particularly in the outer movements, glissandos in the trombones, and blues touches in the Adagio movement.

Ravel may also have injected a certain flavor of his Basque heritage—the first theme of the first movement, for example, has suggested a Basque folk melody to several commentators. Ravel’s imaginative instrumental effects are immediately apparent with this theme, which he gives to the piccolo while the piano furnishes bitonal arpeggios against a soft backdrop of snare drum roll and string tremolos and pizzicatos. The movement’s central andante section, marked “Quasi cadenza,” employs beautiful and unusual harp effects. Also noteworthy are Ravel’s notoriously difficult high horn parts.

The peaceful Adagio comes as a great contrast after the massive descending chords that ended the first movement. Its lovely melody, reportedly inspired by Mozart, is one of Ravel’s best, revealing an interesting ambiguity between 3/4 and implied 6/8 time. After a modulating middle section, the main theme returns in a celebrated English horn solo, accompanied by pianistic figurations.

The fireworks of the finale include much virtuosic display from the pianist and especially challenging orchestral passages, particularly for the bassoons and trumpets. The perpetual motion style, the presto tempo, and the jazz effects make a lighthearted yet brilliant conclusion to Ravel’s “divertissement.”

—©Jane Vial Jaffe

Scored for flute, piccolo, oboe, English horn, clarinet, E-flat clarinet, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, trumpet, trombone, timpani, bass drum, suspended cymbal, snare drum, triangle, tam-tam, wood block, whip, harp, and strings

Tchaikovsky composed the 1812 Overture for the 1882 All Russian Art and Industrial Exhibition, coinciding with the consecration of the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, built to commemorate the Russian defeat of Napoleon in 1812. Tchaikovsky disliked writing music for occasions such as these—“What can you write on the occasion of the opening of an exhibition except banalities and generally noisy passages?” He agreed to do it only if given a very specific commission and an appropriate fee—“when it is a question of an order I am prepared to set an advertisement for corn-plasters to music.”

Tchaikovsky composed the 1812 Overture for the 1882 All Russian Art and Industrial Exhibition, coinciding with the consecration of the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, built to commemorate the Russian defeat of Napoleon in 1812. Tchaikovsky disliked writing music for occasions such as these—“What can you write on the occasion of the opening of an exhibition except banalities and generally noisy passages?” He agreed to do it only if given a very specific commission and an appropriate fee—“when it is a question of an order I am prepared to set an advertisement for corn-plasters to music.”

The actual commission came at the end of September 1880, and Tchaikovsky set to work on October 12. He had completely sketched the 1812 Overture by the following week and he finished the orchestration on November 19. The Exhibition was then delayed for over a year and Tchaikovsky thought there would be no harm in offering the piece to Eduard Nápravnik for a performance in St. Petersburg. The conductor advised him to be patient as it was unethical to be soliciting a performance ahead of the event for which the work had been commissioned. The composer bided his time, and the piece was first performed on August 20 by Ippolit Altani in a hall specially constructed for the Exhibition. Ironically, the 1812 Overture, written with such distaste in October and November 1880, turned out to be one of Tchaikovsky’s most popular pieces.

Working on another of his most famous compositions at the same time, the Serenade for Strings, Tchaikovsky wrote to Nadezhda von Meck, the patroness he never met: “I have written two long works very rapidly: a Festival Overture for the Exhibition and a Serenade in four movements for string orchestra. The Overture will be very noisy.” Indeed, the Overture’s “noise,” including the firing of real cannons at specifically designated moments toward the end, became its most well-known feature. For all its bombast, though, the 1812 Overturecontains passages of real beauty, such as the opening texture of divided violas and cellos in four parts.

Tchaikovsky’s borrowed tunes for the Overture include the Russian national anthem “God Save the Tsar,” the Orthodox chant “Save us, O Lord,” and the folk song “U vorot,” which he had set before for piano duet (1869). He even introduces a duet from his first opera, The Voyevoda, as the start of his second theme. For warring effect, he appropriates the French national anthem, “La Marseillaise,” which he incorporates early in the piece in fragments then more fully in the coda, where it is symbolically silenced by the Russian cannons. He concludes with a grandiose statement of “God Save the Tsar,” adorned with pealing chimes.

—©Jane Vial Jaffe

Scored for 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 cornets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, triangle, tambourine, chimes, cannon, and strings

Described as a “poet of piano” by Le Soir (Belgium), Ukrainian-born American pianist has performed in some of the world’s major concert halls and recently launched his second career as a conductor. He has been praised for “emotional intensity,” “charismatic expression,” “pallette of touches,” “solid,” and “precise technique” by the New York Times, Washington Post,and Miami Herald (US); Gramophone and BBC Music Magazine (UK); and El Pais (Spain). Mr. Khristenko’s performance as a piano soloist with the Lviv National Orchestra of Ukraine in Stern Auditorium at Carnegie Hall has been chosen as one of fifteen highlights of the 2022–23 Carnegie Hall season by the New York Times.

Described as a “poet of piano” by Le Soir (Belgium), Ukrainian-born American pianist has performed in some of the world’s major concert halls and recently launched his second career as a conductor. He has been praised for “emotional intensity,” “charismatic expression,” “pallette of touches,” “solid,” and “precise technique” by the New York Times, Washington Post,and Miami Herald (US); Gramophone and BBC Music Magazine (UK); and El Pais (Spain). Mr. Khristenko’s performance as a piano soloist with the Lviv National Orchestra of Ukraine in Stern Auditorium at Carnegie Hall has been chosen as one of fifteen highlights of the 2022–23 Carnegie Hall season by the New York Times.

Stanislav Khristenko has appeared as a piano soloist with the Cleveland Orchestra; Phoenix, Puerto Rico and Richmond Symphonies; National Orchestra of Belgium; Bilbao, Madrid, and Tenerife Symphony Orchestras; Liege Royal Philharmonic; and Suwon Philharmonic Orchestra, among others. His performance highlights include solo recitals at Carnegie Hall, the Vienna Konzerthaus, and the Palais de Beaux-Arts in Brussels, as well as performances with orchestras at such venues as the Berlin Philharmonie, Seoul Arts Center, Prague Rudolfinum, and Moscow Conservatory Great Hall. His recordings have been released on the Steinway & Sons label (Fantasies and Romeo and Juliet), Naxos (Soler Sonatas), Oehms, and Toccata Classics (Ernst Krenek Piano Works).

In his hometown in Ukraine, Mr. Khristenko initiated the KharkivMusicFest, which in just four years has presented performances of the world’s top musicians as well as vibrant projects such as outreach concerts, painted pianos on streets, the Festival Orchestra, a classical music forum, and the Children’s Orchestra. As a music director, he also founded Nova Sinfonietta Chamber Orchestra, which performed works of over forty composers in its first three seasons.

Stanislav Khristenko is a Steinway Artist.