Concert sponsors:

Joe and Rita Sublett

Doug and Cheryl Hunt

Guest artist sponsors:

Nancy and Ed Schneider

Spanos Companies

Jacques Ibert enlisted in the French navy during the First World War, and his tour of duty took him to several Mediterranean ports. The war interrupted his career as a composer, yet it strengthened his love of travel and his fascination with varied local music traditions. Escales (an escale is a port of call, into which ships put to fill their bunkers with coal or the galley with provisions) was written in 1922 while he was connected with the French Embassy in Rome. The geographical labels do not appear in the score, but they appeared in the program for the premiere and Ibert later admitted to the Courier Musical that the music had been inspired by a Mediterranean cruise during which he had visited Palermo in Sicily, Tunis-Nefta on the African coast, and Valencia in Spain.

“Palermo” opens and closes with what might be a description of gentle waves on the Mediterranean, written with sensuous melodies, rich harmonies, and lush orchestration. The faster middle section is influenced by Italian folk rhythms and dances, especially the tarantella. “Tunis-Nefta,” according to the composer, is based on an air he heard in the Tunisian desert. The chromatic theme is chanted by the oboe “as if prayer beads were unfolded and unrolled,” accompanied by strings and timpani. “Valencia” recalls typically Spanish dance themes, rhythms, and inflections of varied character, building to a fiery conclusion.

Escales was first performed in Paris on January 6, 1924, by the Lamoreaux Orchestra conducted by Paul Paray. It has become one of Ibert’s most frequently heard compositions, comparable in this respect only with his Flute Concerto and Divertissement.

—©Jane Vial Jaffe

Scored for piccolo, 2 flutes, 2nd doubling 2nd piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 3 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, xylophone, field drum, triangle, tambourine, castanets, tam-tam, cymbals, bass drum, 2 harps, celesta, and strings

Max Bruch is one of those unfortunately underrated composers, considered conservative even in his own time. He is known primarily for his G minor Violin Concerto, the present Scottish Fantasy, and Kol nidre for cello and orchestra. The remainder of his output—including three operas, three symphonies, other concertos, chamber music, choral compositions, and songs—is perhaps unjustly overlooked.

When in August 1878 Bruch was selected for the directorship of a choral society in Berlin, he expressed surprise since the Stern’scher Gesangverein had taken no notice of any of his choral works. He really hoped for a position in England, which did come to pass two years later, but meanwhile he took up his duties in Berlin. He worked on just two compositions there, albeit two of his most celebrated—the Scottish Fantasy and Kol nidre.

The Fantasia for the Violin and Orchestra with Harp, freely using Scottish Folk Melodies, better known as the Scottish Fantasy, was written mostly during the winter of 1879–80. Bruch had been inspired, he told musicologist Wilhelm Altmann, by the famous novels of Scottish writer Walter Scott. The composer had been immersed in Scott’s Lady of the Lake, on which his cantata Das Feuerkreuz was based, but with the project postponed indefinitely, he found another outlet for evocations of Scotland.

The Scottish Fantasy was premiered on February 22, 1881, in Liverpool, where Bruch had taken up the position of director of the Philharmonic Society in late August 1880. The celebrated Hungarian violinist Joseph Joachim (also remembered as the close friend of Brahms) played the solo part—according to Bruch, quite badly. But there had been an ongoing struggle in which Bruch was caught between two egotistic violin virtuosos, both of whom he considered his friends. The Scottish Fantasy is, in fact, dedicated to Spanish violinist Pablo de Sarasate and, as Bruch discovered, Joachim was reluctant to play works that were not dedicated to him. Furthermore, Joachim was involved in a grave marital dispute, which may have affected his playing. Joachim, nevertheless, advised him on violin bowings and fingerings before publication.

Bruch struggled over whether to call the work a fantasy or concerto and in the end chose Fantasy because of its free style. Nonetheless, Bruch often referred to the work as a concerto and it appeared as such on various concert programs. Unlike a fantasy, which is often a short, one-movement piece, the Scottish Fantasy consists of four full-fledged movements. The first begins in darkness, with what Bruch told Altmann was meant to evoke “an old bard, who contemplates a ruined castle, and laments the glorious times of old.” The main part of the movement is based on the lovely folk tune “Auld Rob Morris,” lushly scored and given twice.

The tune, “The Dusty Miller,” and also the effect of bagpipe drones lend the proper Scottish atmosphere to the second movement, which Bruch called a dance. “Auld Rob Morris” resurfaces toward the end, leading to the third movement, an introspective Andante sostenuto based on the folk tune “I’m Down for Lack of Johnnie.” The stormier center section of the slow movement gives special prominence to the harp.

Already in his Twelve Scottish Folk Songs (c. 1863) and his First Symphony (1870) Bruch had employed the designation “Allegro guerriero” (warlike allegro), no doubt recalling Mendelssohn’s similar designation for the finale of his Scottish Symphony. Here the direction lends a martial spirit to the Finale’s main theme, based on “Scots wha hae,” which according to legend was sung by the outnumbered but victorious Scots at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. In cyclic fashion, and perhaps to remind the listener of the singing qualities of the violin amidst the pyrotechnics, “Auld Rob Morris” returns for a last wistful remembrance before the final triumphant rendition of “Scots wha hae.”

—©Jane Vial Jaffe

Scored for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, harp, and strings

After earning his bachelor’s degree at the University of Chicago in 1908, Benjamin Casey Allin III pursued an illustrious career in civil engineering, beginning as a surveyor for the Illinois Central Railroad, then for the Board of Insular Affairs in the Philippines, where he also published an English-Philippine dictionary—a nice connection for our Sister Cities concert. He then worked in the production department of the Illinois Steel Company and on bridge evaluation for the Rock Island & Pacific Railway, and he served in both Worlds Wars. In between, in 1919, he was made director of the Port of Houston, where he oversaw the design and construction of what became one of the world’s busiest and most renowned ports. In 1930 he was called to the proposed Port of Stockton as an engineering consultant, later serving as director of the port and chief engineer until 1942. He also consulted on the Port of Bhavnager, India, and the Port of Dalles, Oregon.

An acknowledged expert on the problems of railroads serving ports, Allin patented a system of railroad trackage and wharves. He also standardized terminology in port matters and authored numerous articles on port engineering, including “The Progress of the Port of Stockton, 1856–1935” and “Port of Stockton Developing Plan Balances Warehouse and Berthing Space.” In 1956 he penned his autobiography, Reaching for the Sea.

In his spare time Allin dabbled in music composition, interested primarily in writing music for the Episcopal church, which had attracted him since choirboy days in Chicago. He later held offices in Episcopal churches in Houston and Stockton (St. John’s) and served on the Executive Council of the Province of the Pacific, which included seven Western states. He died in Berkeley, California, where he spent the last fourteen years of his life.

Allin reminisced in his autobiography about venturing outside the composition of church music while in Stockton by writing a four-section piece, Phantasie Philippine, based on a Philippine lullaby he remembered from his time there just out of college. He recalls the piece being played in orchestral guise by the Stockton Symphony and later by a College of the Pacific student for the California Composers and Writers Club. He goes on to say: “Another composition of mine, far different in spirit and more of a musical romp than a serious composition, was the Port of Stockton March [or The Port Stockton March, as the score indicates]. This, too, was played on at least one occasion by the Stockton Symphony to generous applause and my own satisfaction.”

The piano score, unearthed by current Port of Stockton Director Richard Ascheris, notes that the piece was introduced under Manlio Silva’s direction on December 7, 1936, and that it is dedicated to the “the City and the Port of Stockton.” After an annunciatory introduction and a jaunty repeated opening march theme, Allin introduces a minor-mode contrasting section and a grand chordal march before returning to the main march theme of the opening.

Because the orchestral score and parts couldn’t be located in time for the Stockton Symphony’s revival of the work on January 27, 2018, the march was arranged by Peter Jaffe in the Sousa style that Allin’s music suggests. Jaffe added atmospheric touches—chimes suggesting ship bells and chromatic runs evoking swirling winds on the sea—and imaginatively varied the march’s given repeated sections.

On the very eve of the performance, Tod Ruhstaller, director of the Haggin Museum, read the anticipatory article by Lori Gilbert in the Stockton Record and contacted Maestro Jaffe saying the museum had the original orchestral score along with a newspaper account of the “lively and stirring” premiere. As it turns out, the orchestration was not made by Allin but by Hoyle Carpenter—in a different key and with unvaried repeats of all of the march’s sections (not just those prescribed by Allin). Jaffe’s arrangement went on as scheduled and the reception was so enthusiastic that the Port Stockton March was encored on the spot. The following season, the concert honoring Stockton and its sister cities provided the perfect occasion to honor the many requests to hear the piece again.

—©Jane Vial Jaffe

Scored for 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, glockenspiel, chimes, and strings

Respighi’s three symphonic poems celebrating the glories of Rome, his adopted city, became his most popular works: Fountains of Rome (1914), Pines of Rome (1924), and Roman Festivals (1928). Each tests the orchestra’s virtuosity with such masterful scoring that it comes as no surprise to learn that he spent several years in St. Petersburg studying with the great orchestrator Rimsky-Korsakov. Respighi’s Roman Festivals calls for an enormous variety of instruments—among the most colorful are tambourine, ratchet, sleigh bells, tam-tam, glockenspiel, two tubular bells, xylophone, two tavolette (wood blocks), piano (two- and four-hands), organ, three buccine (ancient Roman horns or trumpets), and mandolin. Elsa Respighi, the composer’s wife, wrote in 1954:

The dramatic power and scoring in the first part of Roman Festivals has not been surpassed even today and this reminds me of what Respighi told me as soon as the work was finished: “With the present constitution of the orchestra it’s impossible to achieve more, and I don’t think I shall write any more scores of this kind.”

Roman Festivals was first performed—not in his native Italy but in the United States—by Arturo Toscanini and the New York Philharmonic Society at Carnegie Hall, February 21, 1929. We quote below the full programmatic narrative that Respighi provided as a preface to the score. Clearly the exuberant first section retains its association with Nero, the subject of his 1926 unfinished symphonic poem Nerone, from which he had drawn some of its musical materials.

“1. Circenses [Circus games]: A threatening sky hangs over the Circus Maximus, but it is the people’s holiday. ‘Ave Nero!’ The iron doors are unlocked, the strains of a religious song and the howling of wild beasts float on the air. The crowd rises in agitation. Unperturbed, the song of the martyrs develops, conquers, and then is lost in the tumult.

“2. The Jubilee: The pilgrims trail along the highway, praying. Finally there appears from the summit of Monte Mario, to ardent eyes and gasping souls, the Holy City: ‘Rome! Rome!’ A hymn of praise bursts forth, the churches ring out their reply.

“3. The October Festival: The October festival in the Roman castelli [castles] covered with vines: hunting echoes, tinkling of bells, songs of love. Then in the tender evenfall arises a romantic serenade.

“4. The Epiphany: The night before Epiphany in the Piazza Navona. A characteristic rhythm of trumpets dominates the frantic clamor. Above the swelling noise float, from time to time, rustic motives, saltarello [lively dance] cadences, the strains of a barrel organ from a booth, the barker’s call, the harsh song of the intoxicated, and the lively stornello [verse] in which is expressed the popular feeling: ‘Lassàtece passà, semo Romani!’ (We are Romans, let us pass!)”

—©Jane Vial Jaffe

Scored for 3 flutes, 3rd doubling piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, E-flat clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, 3 buccine (or extra trumpets), mandolin, timpani, glockenspiel, xylophone, tambourine, snare drum, sleigh bells, tenor drum, triangle, ratchet, tam-tam, cymbals, bass drum, chimes, 2 tavolette (wood blocks), piano two- and four-hands, organ, and strings

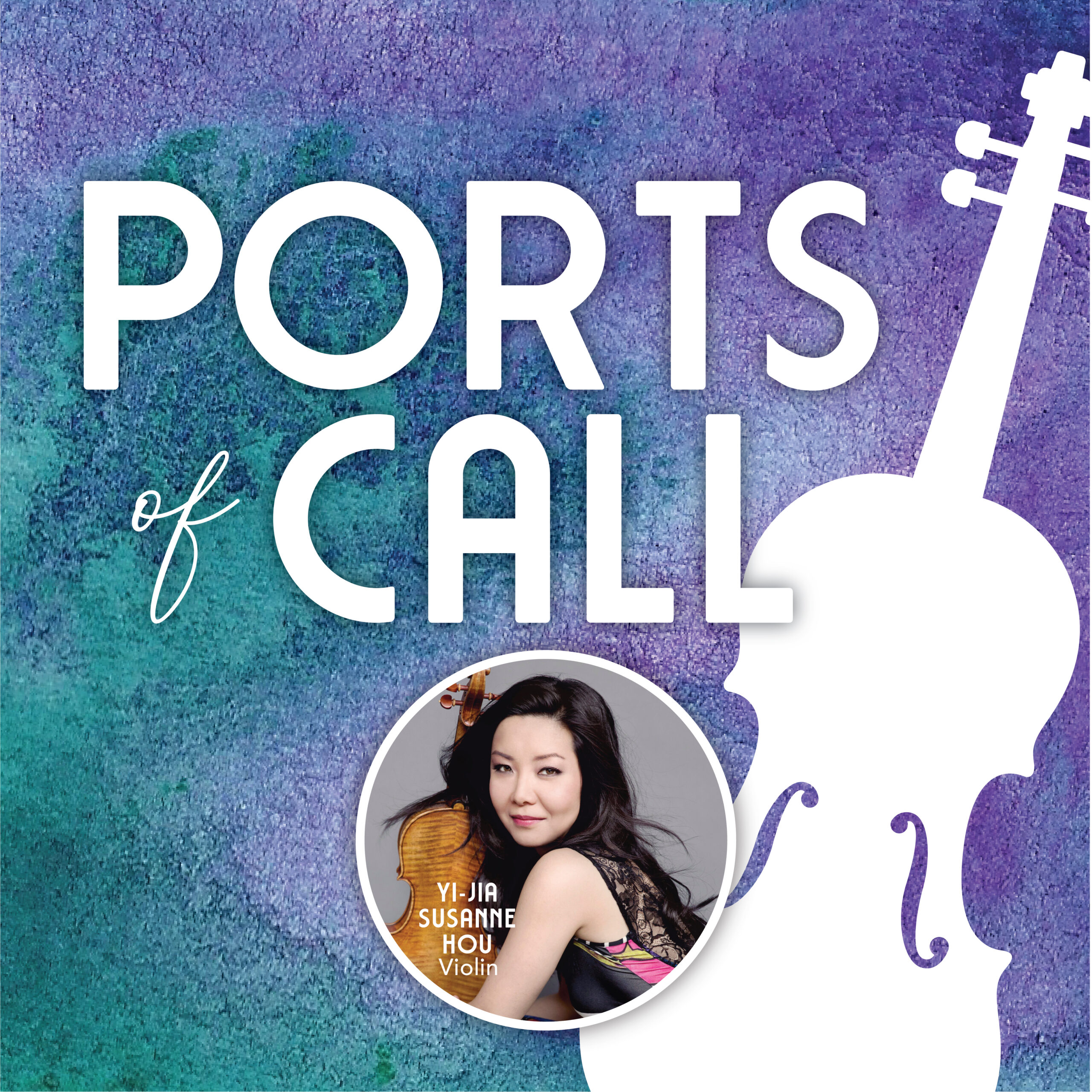

Born to a musical family, Chinese-Canadian violinist Yi-Jia Susanne Hou rose to fame on the international concert scene when she unanimously won three prestigious international violin competitions in France, Italy, and Spain (Long-Thibaud, Lipizer, Sarasate) representing both Canada and China.

Since then Susanne Hou has performed as soloist with major orchestras in over fifty countries including the London Symphony Orchestra, Royal Philharmonic, Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio-France, SWR Stuttgart, WDR Cologne as well as Toronto Symphony, Vancouver Symphony, National Arts Centre Orchestra, Singapore Symphony, Tokyo Philharmonic and NHK. She has collaborated with such renowned musicians as Mstislav Rostropovich, Pinchas Zukerman, Alan Gilbert, JoAnn Faletta, Andreas Delfs, Marek Janowski, Alexander Shelley, Krzysztof Urbański, Hana-Chang, and Gemma New among others.

In 2013 Susanne Hou recorded the Beethoven Violin Concerto with the London Symphony Orchestra playing the outstanding 1735 ex-Fritz Kreisler Mary Portman Guarneri Del Gesù violin as a tribute to its unique history. In 2016 she performed and recorded the Butterfly Lovers Violin Concerto with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and conductor John Nelson at London’s Cadogan Hall, a work she successfully toured with in China and Taiwan.

Her recent and future engagements include German tour with Sinfonietta Cracovia, a return to the Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra; an extensive recital and concert tour to South Africa working with the Cape, Johannesburg, and Kwazulu Natal Philharmonic Orchestras; a recital at Flaneries Musicales de Reims; and concerts with the Hamilton Philharmonic Orchestra and Vancouver Symphony Orchestra in Canada as well as the Folsom Lake Symphony and Stockton Symphony in the US.

Yi-Jia Susanne Hou is a passionate advocate for music education. She consistently engages in creative projects involving early classical music coaching as well as mentoring aspiring young artists. Launched in 2017, her education initiative called “3-degrees” began in Brazil where she worked with inspired musical students from underprivileged backgrounds. Subsequently, she partnered with DakApp bringing young artists from the Juilliard School in New York, Royal College of Music in London, Beijing Central Conservatory, and Paris Conservatoire to London for the filming of a masterclass, with orchestra, which is now available online via DakApp to students all over the world.