Concert sponsors: Zeiter Eye Medical Group, Inc.

Guest artist sponsors: John and Francesca Vera

Jan and Mike Quartaroli

Diane Ditz Stauffer

Piano tuning by Weiner Piano Service

Guest artist accommodations: Hal and Debbie Lurtsema

Poland’s most outstanding woman composer of the twentieth century, Grażyna Bacewicz first won great renown in Europe as a violinist. Only recently have her compositions begun to gain attention in the United States. She received her earliest training in violin and piano from her father and wrote her first composition at age thirteen. After studying violin, piano, and theory at a local conservatory in Łódź, she transferred to the Warsaw Conservatory where she received diplomas in violin and composition in 1932. Like so many other musicians, she continued her studies in Paris—composition with Nadia Boulanger and violin with André Touret and Carl Flesch. As a composer, she absorbed the Neoclassic style so prevalent in Paris, though she objected to that label for her music.

Poland’s most outstanding woman composer of the twentieth century, Grażyna Bacewicz first won great renown in Europe as a violinist. Only recently have her compositions begun to gain attention in the United States. She received her earliest training in violin and piano from her father and wrote her first composition at age thirteen. After studying violin, piano, and theory at a local conservatory in Łódź, she transferred to the Warsaw Conservatory where she received diplomas in violin and composition in 1932. Like so many other musicians, she continued her studies in Paris—composition with Nadia Boulanger and violin with André Touret and Carl Flesch. As a composer, she absorbed the Neoclassic style so prevalent in Paris, though she objected to that label for her music.

Back in Warsaw, Bacewicz taught at the Łódź Conservatory and in 1935 won the prestigious Wieniawski International Violin Competition. She then served for two years as concertmaster for the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra. Her career as a composer grew just as quickly, and her role as a performer helped promote her works—she premiered most of her violin concertos and even some of her piano works.

In September 1939 Hitler’s troops invaded Poland, and all of Bacewicz’s public musical activities came to a halt. Her family was moved first to a displaced persons camp on the outskirts of Warsaw and then to Lublin a hundred miles away. She continued to perform in secret and to compose, managing to create some of her major works, such as her String Quartet No. 2, Sonata No. 1 for solo violin, First Symphony, and the present Overture. As soon as the War ended she fully resumed her musical activities and rolled out premieres of all the works the she had composed during the occupation. When Poland came under control of the Soviet Union, she complied with the directive to include folk elements in her music, but her compositions remained remarkably free of political overtones.

By this time Bacewicz had moved on from her earlier Neoclassic tendencies to a stronger personal style with a chromatically based approach to harmony and intricate rhythmic procedures. She had already begun to curtail her performing when in 1954 she was further hampered by injuries from a car accident. In the late 1950s she dabbled in the inescapable avant-garde trends from abroad, though without conviction, and returned to her own imaginative musical language, eventually incorporating self-borrowing. To top off her multifacted career, she began writing short stories, novels, and anecdotes about her life, and from 1966 until her death she taught composition at the National Higher School of Music (now the Chopin University of Music) in Warsaw.

Composed in 1943, Bacewicz’s Overture was premiered as soon as the War was over at the quickly organized Kraków Festival of Contemporary Music on September 1, 1945, with the Kraków Philharmonic, conducted by Mieczysław Mierzejewski. With two blazing fast sections surrounding a serene oasis, the brief Overture begins with a pattern of short-short-short-long timpani motives soon camouflaged by bustling strings. The rhythm corresponds to Morse code for “V,” which stood for “Victory” during the War, and by chance to the famous opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, which became a powerful symbol for the Allied forces. Though Bacewicz was averse to making programmatic or political statements in her music, commentators wonder if she made an exception here.

With two blazing fast sections surrounding a serene oasis, the overall impression of the Overture is one of unbridled optimism. The outer sections bristle with virtuosic writing for the strings but also for the winds and brass, and the lyrical middle contains a meltingly beautiful flute melody as well as expressive lines for the horns and violas. Often referred to as pastoral, this respite could just as easily bring to mind a lovely park in Paris. The propulsive energy returns abruptly, launching a masterful buildup to the finish.

—©Jane Vial Jaffe

Scored for 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, suspended cymbal, triangle, glockenspiel, and strings

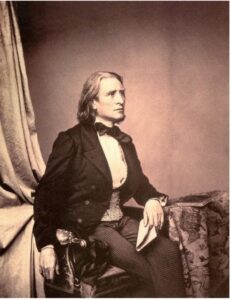

As a celebrated young piano virtuoso, Liszt made a few sketches for his First Piano Concerto in 1830. He did not begin work in earnest, however, until 1849 in Weimar, where he had accepted the position of Court Kapellmeister the previous year. Still not satisfied, he reworked the Concerto in 1853 and finally prepared it for a public performance on February 17, 1855. On this auspicious occasion Liszt himself was the soloist with none other than Berlioz as conductor. The Concerto met with great enthusiasm, although it must be said that Liszt was such a persuasive performer that the audience would have adored anything he played. He felt, however, that further revisions were necessary, which he undertook in 1856.

As a celebrated young piano virtuoso, Liszt made a few sketches for his First Piano Concerto in 1830. He did not begin work in earnest, however, until 1849 in Weimar, where he had accepted the position of Court Kapellmeister the previous year. Still not satisfied, he reworked the Concerto in 1853 and finally prepared it for a public performance on February 17, 1855. On this auspicious occasion Liszt himself was the soloist with none other than Berlioz as conductor. The Concerto met with great enthusiasm, although it must be said that Liszt was such a persuasive performer that the audience would have adored anything he played. He felt, however, that further revisions were necessary, which he undertook in 1856.

Critics have periodically taken the work to task for empty virtuosity, and the opinionated Viennese critic Eduard Hanslick lampooned it as a “triangle concerto,” simply because Liszt had written a triangle part when traditional concertos had none. Fashions and tastes change, however, and the compelling Concerto has triumphantly survived them all.

Liszt was extraordinarily preoccupied with both the idea of combining several movements in one and the related idea of cyclic form, in which the same musical material appears in more than one movement. In both regards he was profoundly influenced by the example of Schubert, whose celebrated Wanderer Fantasy for piano four hands Liszt knew well and had arranged for piano and orchestra in 1851. He was also well aware of the cyclic properties of Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique, which he had transcribed for piano in 1834.

Liszt’s Concerto No. 1 consists of four sections played continuously. The sections resemble the forms of a Classic symphony and indeed Liszt referred to them as such in his correspondence. None is developed completely in the Classic style, however, and throughout Liszt ingeniously transforms and develops themes that have been heard before.

The bold opening theme sets the bravura tone of the work but also prepares the listener for a harmonic adventure, since it immediately changes keys. The phrase also serves as a motto that unifies the entire Concerto. Apparently Liszt and the conductor Hans von Bülow fit words to it: “Das versteht ihr alle nicht, haha!” (None of you understand this, haha!)—which may refer to the form, harmonies, or the challenging piano part. This section has hardly begun when the pianist plays a brilliant cadenza, only one of many such passages of virtuosic display.

The strings briefly present the lovely melody of the “slow movement” (Quasi adagio) before the piano alone plays a fuller version. The atmosphere of serenity undergoes an amazing transformation when Liszt reuses the theme in the final section. After the appearance of contrasting material, the return of the lyrical theme in the clarinet suggests a ternary shape. In Liszt’s condensed form, however, the “scherzo” begins instead, signaled by the triangle that so provoked Hanslick.

The “scherzo” is also truncated, in this case by a piano cadenza and a transition, both of which develop the motto theme from the opening. The main theme of the Quasi adagio returns in the guise of a spirited march to begin the finale. “The fourth movement of the Concerto,” the composer wrote to his cousin with pride, “is only an urgent recapitulation of the earlier material with quickened, livelier rhythm, and it contains no new motives. . . . This kind of binding together and rounding off a piece at its close is somewhat my own, but it is quite organic and justified from the standpoint of musical form.” Motives from the Quasi adagio reappear, the main scherzo motive is treated extensively, and finally the motto theme returns. With a torrent of pounding octaves, the soloist concludes the Concerto in a blaze of glory.

—©Jane Vial Jaffe

Scored for 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, triangle, cymbals, and strings

Dvořák endured three homesick years in New York beginning in 1892, having been persuaded by the iron-willed, progressive Jeannette M. Thurber to serve as director of the National Conservatory of Music that she had founded in 1885. She hoped he would write an American opera based on Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha, which he already knew from a Czech translation, but his thoughts turned instead toward a symphony. His fascination with the epic poem is documented in five notebooks in which he kept dated and undated ideas for compositions. The first entry (December 1892) contains the melody of the middle section of the slow movement of the New World Symphony, under the heading “Legend.” Other ideas for the first three movements came to him in January 1893 and the entire Symphony was completed by May 24. That same day he received the wonderful news by cable that his four children had arrived in Southampton on their way to spend the summer in America. The story that in his excitement he forgot to complete the trombone parts has been shown to be a myth.

Dvořák endured three homesick years in New York beginning in 1892, having been persuaded by the iron-willed, progressive Jeannette M. Thurber to serve as director of the National Conservatory of Music that she had founded in 1885. She hoped he would write an American opera based on Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha, which he already knew from a Czech translation, but his thoughts turned instead toward a symphony. His fascination with the epic poem is documented in five notebooks in which he kept dated and undated ideas for compositions. The first entry (December 1892) contains the melody of the middle section of the slow movement of the New World Symphony, under the heading “Legend.” Other ideas for the first three movements came to him in January 1893 and the entire Symphony was completed by May 24. That same day he received the wonderful news by cable that his four children had arrived in Southampton on their way to spend the summer in America. The story that in his excitement he forgot to complete the trombone parts has been shown to be a myth.

The New York Philharmonic, conducted by Anton Seidl, premiered the work on December 15, 1893. Dvořák, who hated public display, was given an overwhelming ovation, which he described to his publisher Simrock:

The papers say that no composer ever celebrated such a triumph. Carnegie Hall was crowded with the best people of New York, and the audience applauded so that, like visiting royalty, I had to take my bows repeatedly from the box in which I sat. It made me think of Mascagni in Vienna.

Earlier that year Simrock had asked Brahms to proofread several of Dvořák’s works including the New World, which he wanted to publish as quickly as possible. Dvořák was so honored by Brahms’s agreement that he wrote Simrock, “I can scarcely believe there is another composer in the world who would do as much.”

Initially the Symphony’s nickname caused much discussion, though Dvořák insisted that all it meant was “Impression and Greetings from the New World.” Before the premiere Dvořák stated that future American music should be based on black spirituals and American Indian songs and dances. He had become acquainted with spirituals as sung to him by Henry T. Burleigh, one of the African-American students at the National Conservatory, and “knew” American Indian music only from a small number of transcriptions he had been given. “They are the folk songs of America, and your composers must turn to them. In the Negro melodies of America I discover all that is needed for a great and noble school of music.”

Back in Europe he later denied that his Symphony was based on such music; the truth lies somewhere in between. In any case, the similarities to folk and spiritual elements in his Symphony were soon analyzed by many: the first movement’s second theme, introduced by flute, bears a similarity to “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot”; the English horn solo in the slow movement has the character of a spiritual; and the Scherzo, Dvořák himself said before the premiere, “was suggested by the wedding feast in Hiawatha where Indians dance, and is also an essay that I made in the direction of imparting the local color of Indian character to the music.”

The composer used specific elements of then-current American musical vocabulary—such as syncopations and lowered seventh degrees in the minor scale (later to appear in blues)—but synthesized them in his own style. Many supposed that the famous English horn solo in the Largo quoted an existing spiritual “Going Home,” but the order is the reverse—Dvořák wrote it first. Seidl said, “It is not a good name, New WorldSymphony! It is homesickness, home longing.” Dvořák’s Bohemian roots are certainly evident, for instance the middle sections of the Largo sound more Czech than American and the Scherzo could just as easily depict Czech dances as American Indian.

Dvořák’s sketches show that he originally thought of the first movement’s main theme, the great arching horn fanfare, in F major. When he later settled on E minor, he wrote a sketch for the slow movement in C major, a third-related key that was quite normal for him. He had, however, first thought of the movement’s beautiful English horn solo in D-flat major (related by third to his original F major) and discovered that by means of a now celebrated modulation he could retain his original colorful key. Thus he ended up with a wonderfully remote key relationship between the first two movements.

Another structural nicety, however, was part of Dvořák’s concept from the start: the first movement’s second theme (the “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot”–like theme) first appears naturally in G major, the relative of the home key (E minor), yet the entire passage occurs in the distant key of A-flat major in the recapitulation—a novel harmonic idea. Dvořák was well into the sketch for the Scherzo before the master stroke occurred to him to make the symphony cyclic by recalling the horn theme of the first movement in each subsequent movement. He then had to make changes in the slow movement, and the Scherzo itself recalls both the main themes of the first movement in its coda. He further bound his Symphony together thematically by weaving subjects from all previous movements into the finale.

—©Jane Vial Jaffe

Scored for 2 flutes, 2nd doubling piccolo, 2 oboes, 2nd doubling English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, triangle, cymbals, and strings

Italian native Roberto Plano performs regularly throughout North America and Europe—notably at Lincoln Center, Sala Verdi, Salle Cortot, Wigmore Hall, and the Herkulessaal. He has appeared with orchestras all over the world, under the direction of renowned conductors such as Neville Marriner, James Conlon, Pinchas Zuckerman, and Miguel Harth-Bedoya. He has been a featured recitalist at the internationally acclaimed Newport Festival, the Portland Piano Festival, Ravinia Festival and the Gilmore International Keyboard Festival (US), Chopin Festival (Poland), the Bologna Festival–Great Soloists (Italy), and many others. He has played with string quartets such as the Takács, Cremona, St. Petersburg, Fine Arts, Jupiter, and Muir, as well as soloists such as Ilya Grubert, Pavel Berman, Jiri Barta, Enrico Bronzi, and in duo with his wife Paola Del Negro.

Italian native Roberto Plano performs regularly throughout North America and Europe—notably at Lincoln Center, Sala Verdi, Salle Cortot, Wigmore Hall, and the Herkulessaal. He has appeared with orchestras all over the world, under the direction of renowned conductors such as Neville Marriner, James Conlon, Pinchas Zuckerman, and Miguel Harth-Bedoya. He has been a featured recitalist at the internationally acclaimed Newport Festival, the Portland Piano Festival, Ravinia Festival and the Gilmore International Keyboard Festival (US), Chopin Festival (Poland), the Bologna Festival–Great Soloists (Italy), and many others. He has played with string quartets such as the Takács, Cremona, St. Petersburg, Fine Arts, Jupiter, and Muir, as well as soloists such as Ilya Grubert, Pavel Berman, Jiri Barta, Enrico Bronzi, and in duo with his wife Paola Del Negro.

Plano was the first-prize winner at the 2001 Cleveland International Piano Competition; prizewinner at the Honens, Dublin, Sendai, Geza Anda, and Valencia Competitions; and finalist at the 2005 Van Cliburn and Busoni Competitions, in addition to having won fifteen first prizes in national competitions in Italy. In 2018 he won the American prize in the solo professional division. Plano’s engaging personality has made him a favorite guest on radio programs such as NPR’s Performance Today.

Among his more than twenty commercial CDs, Plano’s recent debut recording with Decca Classics features Liszt’s Harmonies poétiques et religieuses, which have not been recorded by Decca since the ’60s. He has also recently recorded several world-premiere CDs with music of Andrea Luchesi (1741–1801), whose two piano concertos Plano premiered with the Busoni Chamber Orchestra in Trieste, Italy. Plano’s other recent highlights include solo appearances with Kremerata Baltica in Italy, the Royal Camerata in Bucharest, and the Boston Civic Symphony, as well as recitals and chamber music concerts in South Africa, Taiwan, Lithuania, Spain, and at the Boston Athenaeum. He was also invited to perform in Russia, including two concerts at the Kremlin State Palace in Moscow, and on tour in China with Juilliard faculty members Laurie Smukler and Darrett Adkins.

Plano studied at the Verdi Conservatory in Milan, the Ecole Normale “Cortot” in Paris, and the Lake Como Academy. Now one of the most sought-after teachers in the world, he served on the faculties of Boston University and the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music until 2023 when he joined the faculties of the Conservatorio della Svizzera Italiana (Lugano, Switzerland) and the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester (UK). He also regularly teaches during the summer at the Rebecca Penneys Piano Festival and the Kneisel Hall Chamber Music Festival.