Concert cosponsors: Ann and Philip Berolzheimer, Rita and Joe Sublett, Zeiter Eye Medical Group, Inc.

Guest artist cosponsors: Conni Bock, Honorable Ann Chargin, Jan and Mike Quartaroli

Piano tuning by Weiner Piano Services

Gabriela Lena Frank serves as composer-in-residence with the Philadelphia Orchestra and in 2017 was named by the Washington Postas one of the thirty-five most significant woman composers in history. Of Peruvian/Chinese descent on her mother’s side and Lithuanian/Jewish heritage on her father’s, Gabriela Lena Frank most often draws on the folklore and musical styles of Latin American in her own compositions. Having grown up in Berkeley, California, and having earned music degrees at Rice University in Texas and the University of Michigan, she combines her Latin American folk inspirations with her American training, during which she was profoundly influenced by Ginastera and Bartók.

Frank’s unique perspective has brought her extraordinary success, with regular commissions for some of the world most prominent performers—cellist Yo Yo Ma, soprano Dawn Upshaw, the King’s Singers, and the Kronos Quartet, among others. She has also received orchestral commissions and performances from the renowned symphony orchestras of Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia, Atlanta Symphony, Cleveland, and San Francisco. More recently Frank’s first opera—The Last Dream of Frida and Diego to words by Pulitzer Prize–winning Cuban poet Nilo Cruz—received its premieres between 2020 and 2023 by its co-commissioners, Fort Worth Opera, Depauw University, San Diego Opera, and San Francisco Opera. Most recently her Concerto grosso for the Takàcs Quartet premiered in July 2024.

Recipient of the prestigious Heinz Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a USA Artist Fellowship, Frank won a Latin Grammy for her Inca Dances for guitarist Manuel Barrueco and the Cuarteto Latinoamericano. She has been featured in several scholarly books and PBS specials, including the Emmy-nominated Música Mestiza by filmmaker Aric Aric. Born with high-moderate/near-profound hearing loss, Frank has also written for the New York Times about how Beethoven’s deafness affected his music.

Frank has held myriad composer residencies, completing those with the Detroit and Houston Symphonies just prior to that with the Philadelphia Orchestra. She is also an accomplished pianist and highly involved in community outreach. She has volunteered in hospitals and prisons, worked with deaf students to rap in sign language, and, in 2017, founded the Gabriela Lena Frank Creative Academy of Music, a much-lauded nonprofit institution that offers training for emerging composers from diverse cultural backgrounds, opportunities to work with underrepresented students in rural communities, and professional commissioning avenues for alums.

Frank writes about the present work, premiered by the Philadelphia Orchestra on October 25, 2012: “Concertino cusceño, written to celebrate the fine players of the Philadelphia Orchestra on the eve of Yannick Nézet-Ségun’s inaugural season as music director, finds inspiration in two unlikely bedfellows: Peruvian culture and British composer Benjamin Britten. As a daughter of a Peruvian immigrant, I’ve long been fascinated by my multicultural heritage and have been blessed to find Western classical music to be a hospitable playpen for my wayward explorations. In doing so, I’ve looked to composers such as Alberto Ginastera from Argentina, Béla Bartók from Hungary, Chou Wen-chung from China, and my own teacher William Bolcom from the US as heroes: To me, these gentlemen are the very definition of ‘cultural witnesses,’ as they illuminate new connections between seemingly disparate idioms of every hue imaginable.

“To this list, I add Britten, whom I admire inordinately. I wish I could have met him, worked up the nerve to show him my own music, invited him to travel to beautiful Perú with me. I would have shared chicha morada (purple corn drink) with him, taken him to a zampoña panpipe instrument–making shop, set him loose in a mercado (market) streaming with immigrant Chinos and the native Indio descendants of the Incas. I would have loved showing him the port towns exporting anchoveta (anchovies), the serranos (highlands) exporting potatoes, and the selvas (jungles) exporting sugar. And I know Britten would have been fascinated by the rich mythology enervating the literature and music of this small Andean nation, so deeply similar to the plots of his many operas, among other works.

“Concertino cusqueño melds together two brief musical ideas: The first few notes of a religious tune, ‘Collanan María,’ from Cusco (the original capital of the Inca empire Tawantinsuyu, and a major tourist draw today) with the simple timpani motive from the opening bars of the first movement of Britten’s elegant Violin Concerto. I am able to spin an entire one-movement work from these two ideas, designating a prominent role to the four string principal players (with a bow to the piccolo/bass clarinet duo and, yes, the timpanist). In this way, while imagining Britten in Cusco, I can also indulge in my own enjoyment of personalizing the symphonic sound by allowing individuals from the ensemble to shine.

“It is with further joy that I dedicate this piece to my nephew Alexander Michael Frank, born in Philadelphia on February 25, 2011.”

—©Jane Vial Jaffe

In June 1868 Grieg traveled with his wife Nina and baby daughter to Denmark to undertake his largest-scale work to date, a work for piano and orchestra. Notorious for his inability to work with the slightest outside disturbances, Grieg settled down in the picturesque town of Sölleröd while Nina and the baby went to Nina’s parents in Copenhagen. Two of Grieg’s friends were with him in Sölleröd—publisher/composer Emil Horneman and virtuoso pianist Edmund Neupert, who consulted with the composer as the work took shape. It was only natural that Neupert should receive the dedication and play the first performance, which was scheduled for shortly after Christmas.

Though the Concerto was completed in rough form at Sölleröd, the orchestration had to be fit around Grieg’s many other duties that fall and winter in Oslo. This proved so difficult that the premiere had to be postponed until April 3, 1869, when Neupert indeed played the solo part with the Royal Theater Orchestra in Copenhagen, conducted by Holger Simon Paulli. It was a major event: Queen Louise was in attendance, as were the leading musical personalities, including Johann Peter Emilius Hartmann, Niels Gade, and world-famous Russian virtuoso pianist Anton Rubinstein, who had lent his own grand piano for the occasion. On April 6 Neupert wrote to Grieg who had been unable to attend:

On Saturday your divine Concerto resounded through the Casino’s large auditorium. The triumph I received was really tremendous. Already at the conclusion of the cadenza in the first part the audience broke out in a true storm [of applause]. The three dangerous critics—Gade, Rubinstein, and Hartmann—sat up in the loge and applauded with all their might.

I am supposed to greet you from Rubinstein and tell you that he is really surprised to have heard such a brilliant composition; he looks forward to making your acquaintance.

The Concerto soon won international fame and has achieved the same kind of ultra-popularity as Tchaikovsky’s B-flat minor Piano Concerto. At a now-famous meeting between Grieg and Liszt in Rome in 1870, Liszt fulfilled Grieg’s expectations by reading Grieg’s Concerto at sight. “He played the cadenza, the most difficult part, best of all,” wrote Grieg. “Not content with playing, he, at the same time, converses and makes comments, addressing a bright remark now to one, now to another of the assembled guests, nodding significantly to the right or left, particularly when something pleases him.” Liszt was delighted with Grieg’s Concerto and Grieg incorporated some of his suggestions when it was published in 1872.

Grieg greatly admired Schumann’s Piano Concerto in the same key and claimed that he studied it in depth before writing his own. He followed Schumann’s model in regard to an opening fanfare for the pianist, and in certain formal respects, but he created a completely independent work—one that contains specifically Norwegian elements. One of these occurs between the main theme and second theme, a transitional passage containing rhythms of the halling, a lively Norwegian folk dance in duple meter. Grieg’s reputation as a melodist is reaffirmed by the lyrical second theme, which since an 1882 edition has been played by the cellos, as opposed to the trumpet in the manuscript and early editions. Grieg continued to tinker with the Concerto throughout his life, making final revisions as late as 1906–07.

The tender, nocturnal slow movement follows a simple A-B-A pattern, leading without pause into the finale through a magical dialogue between the piano and solo horn. The nationalistic character of the last movement is evinced through the main theme in the piano, again reminiscent of the halling. Grieg scholar Schjelderup-Ebbe also likens the use of pedal point, open fifths, and sharp dissonances to the sounds of the Hardanger fiddle. The halling refrain near the end is transformed into another folk-dance rhythm, that of the springar in 3/4 meter. It was the concluding climax of the movement with its sudden use of the flattened leading tone that so excited Liszt in 1870. Grieg reported:

Toward the end of the finale the second theme is, as you may remember, repeated in a mighty fortissimo. In the very last measures, when in the first triplets the first tone is changed in the orchestra from G-sharp to G, while the piano part, in a mighty scale passage, rushes wildly through the whole reach of the keyboard, he [Liszt] suddenly stopped, rose up to his full height, left the piano, and with big, theatric strides and arms uplifted walked across the large cloister hall, at the same time literally roaring the theme. When he got to the G in question he stretched out his arms imperiously and exclaimed “G, G, not G-sharp! Magnificent! That’s the real Swedish article!” . . . He went back to the piano, repeated the whole strophe, and finished. In conclusion he handed me the manuscript and said in a peculiarly cordial tone: “Keep steadily on: I tell you, you have the capability, and—do not let them intimidate you!”

—©Jane Vial Jaffe

Scored for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, and strings

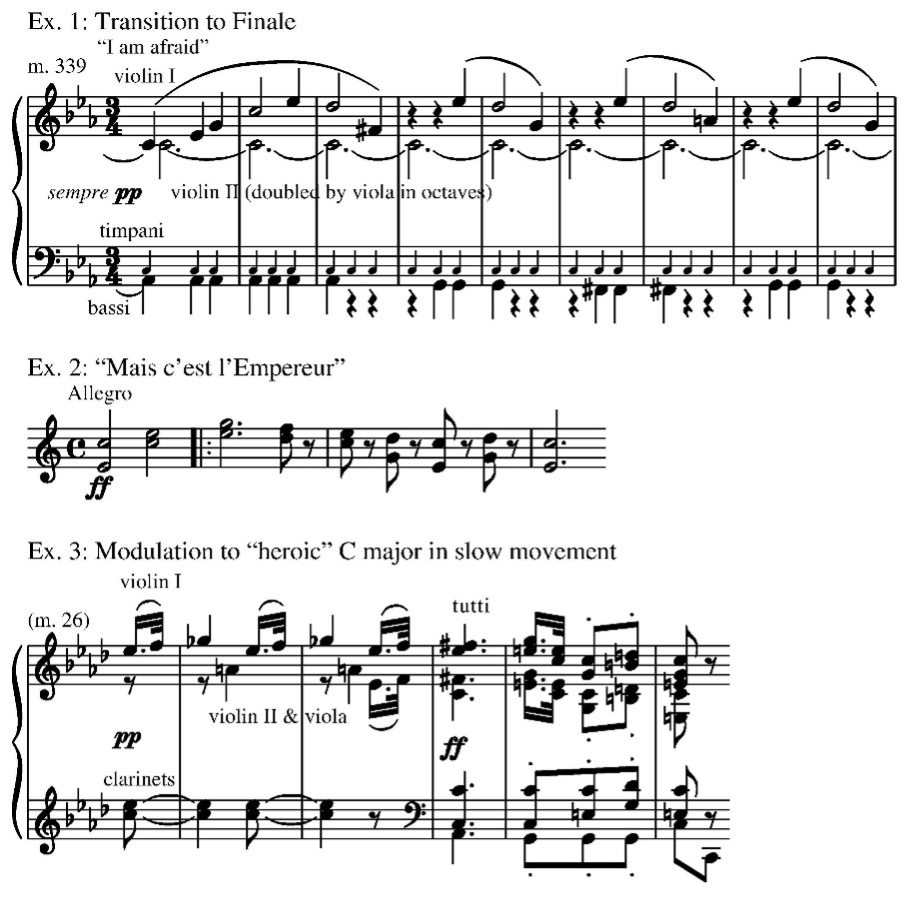

The immense popularity of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony has dulled our senses to the boldness and originality of the work, which initially caused a certain resistance. The great Goethe could not appreciate it, remarking that “it is merely astonishing and grandiose.” Even in 1843, thirty-five years after its premiere, a critic wrote of the celebrated transition from the scherzo to the finale: “There is a strange melody, which, combined with an even stranger harmony of a double pedal point in the bass on G and C, produces a sort of odious meowing, and discords to shatter the least sensitive ear.” (See Example 1.) Equally astonishing were the “oboe cadenza” in the first movement, the addition of piccolo, contrabassoon, and three trombones to the finale, and the return of the scherzo in the finale.

Many features have contributed to the eventual superstar status of “the Fifth.” The opening motive, which Beethoven reportedly explained to his friend and biographer Anton Schindler as “Thus Fate knocks at the door!,” has provided dramatic associations to generations of listeners. In World War II, for example, it was used as a symbol of resistance to fascism. Though Beethoven left no programmatic explanations linking his Symphony to political events of the early nineteenth century, the work is a product of his heroic style—his patriotic and anti-Napoleonic sentiments had reached their height at this time. The patriotism expressed in his music resonated within people of many different historical periods and nations, even the very forces Beethoven saw as the oppressor. A veteran of Napoleon’s army hearing the work in 1828 is said to have exclaimed at the beginning of the finale: “Mais c’est l’Empereur!” (But it’s the Emperor!) (See Example 2.)

The Fifth has also aroused certain unnamed terrors in its listeners, an aspect already sensed by Goethe and Romantic writer E.T.A. Hoffmann. Robert Schumann reported that a child whose hand he was holding during a performance of the Fifth whispered “J’ai peur” (I’m afraid) at the chilling transition from the scherzo to the finale. (Refer back to Example 1.) Hector Berlioz commented on the “stunning” effect of this transition saying it would be impossible to surpass it in what follows. Yet the allaying of the terrors by the triumph of the C major finale has gained the Symphony almost as many admirers as the opening motive.

Like many of Beethoven’s works, the Fifth had a long gestation period: sketches from early 1804 appear amid those for the Fourth Piano Concerto and the first act of Leonore (later titled Fidelio); more sketches appeared later in 1804, and by 1806 advanced sketches for all the movements took shape near those for the Violin Concerto and Cello Sonata in A major. Beethoven then interrupted work on the Fifth for another symphony, the Fourth, commissioned by Count Oppersdorf. The Fifth occupied the composer in 1807, and he finally completed it in the spring of 1808. Count Oppersdorf apparently expected this dedication too, but Beethoven dedicated the Fifth to two other patrons, Prince Lobkowitz and Count Razumovsky.

The Fifth Symphony was first performed on that historic, more-than-four-hour concert at the Theater-an-der-Wien on December 22, 1808—an all-Beethoven program consisting mainly of newly composed works: the Fifth and Sixth symphonies conducted by the composer, the Fourth Piano Concerto in which Beethoven performed the solo part, the aria “Ah! perfido” (1795–96), three numbers from his Mass in C major, op. 86, his own improvisations, and the quickly composed Choral Fantasy, op. 80. By all accounts the preparations for this concert had been extremely problematic, Beethoven himself contributing a large share of the difficulties; the concert consequently produced mixed results.

The Fifth Symphony has been performed countless times since then, and its influence cannot be underestimated. But no matter how many times we may have heard the work, it continues to surprise and delight. The first movement is remarkable for its concentrated rhythmic development, based on the opening rhythm, short-short-short-long: . This rhythm appears in more than half of the movement’s measures, with captivating, ingenious transformations. Beethoven unified the entire Symphony with further developments of the same rhythm. We hear it in the second theme of the slow movement and in the fortissimo horn call that answers the haunted opening of the scherzo. It recurs in the further development of the “call,” including its insistence in the famous transition to the last movement, and reappears in the finale’s development section and the ensuing recall of the scherzo.

The slow movement provides a certain relaxation from the heroic style, but even here the dotted rhythms can sound martial and the ending of the first phrase receives a heroic stress. Even more striking is the valiant blaze of C major into which Beethoven has modulated during the course of the second theme. (See Example 3.) The double variation form—two alternating sections, each varied, plus coda—is remarkable for its move from literal variation to a free, more improvisatory style of variation.

The scherzo contains the aforementioned stealthy and heroic elements in its first section, followed by an energetic trio in fugato (imitative) style and a shadowy, abbreviated return to the scherzo section. After the suspense of the transition, the finale bursts forth triumphantly. Beethoven had originally intended for the trio and scherzo to be repeated as in the Fourth Symphony (scherzo-trio-scherzo-trio-scherzo) rather than to follow the conventional scherzo-trio-scherzo layout, but scholars have concluded that the latter represents his “final version,” perhaps justified in the larger scheme by the formal integration with the last movement.

The addition of piccolo, contrabassoon, and trombones—for the first time in symphonic history—contributes to the triumphal character of the finale. The use of sonata form here shows Beethoven’s continued concern for giving his last movement equal weight with his first. The unexpected return of the scherzo in this movement gives Beethoven another chance to show transcendence over adversity, symbolized by the recapitulation grandly banishing the stealthy strains. Further it gave him a good reason—that of balance—to include a prolonged affirmation of the major home key in the coda. Symphonic thought had entered a new era.

—©Jane Vial Jaffe

Scored for 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, and strings

Venezuelan pianist Gabriela Martinez has a reputation for the lyricism of her playing, her compelling interpretations, and her elegant stage presence. Her playing has been described as “magical . . . a remarkable pianist with a cool determination, a tone full of glowing color and a seemingly effortless technique” (Mark Swed, Los Angeles Times) and “compelling . . . versatile, daring and insightful” (New York Times).

Venezuelan pianist Gabriela Martinez has a reputation for the lyricism of her playing, her compelling interpretations, and her elegant stage presence. Her playing has been described as “magical . . . a remarkable pianist with a cool determination, a tone full of glowing color and a seemingly effortless technique” (Mark Swed, Los Angeles Times) and “compelling . . . versatile, daring and insightful” (New York Times).

Gabriela made her orchestral debut at age six and has since performed with over 100 orchestras including the San Francisco, Chicago, Houston, San Diego, Grand Rapids, New Jersey, Tucson, Pacific, and Fort Worth symphonies; the Buffalo Philharmonic; Germany’s Stuttgarter Philharmoniker, MDR Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestra, and Nurnberger Philharmoniker; Canada’s Victoria Symphony Orchestra; the Costa Rica National Symphony; and the Simon Bolivar Symphony Orchestra in Venezuela. She has performed with Gustavo Dudamel, James Gaffigan, James Conlon, JoAnn Falleta, Michael Francis, Marcelo Lehninger, and Guillermo Figueroa, among many others.

Passionate about new music, Gabriela has commissioned and premiered works by many composers including Mason Bates, Sarah Kirkland Snider, Paola Prestini, Jessica Meyer, and Dan Visconti. Gabriela’s debut album, Amplified Soul (Delos) was recognized with a Grammy Award for Producer of the Year, David Frost.

Gabriela has performed at such venues as Carnegie Hall, Avery Fisher Hall, Merkin Hall, and Alice Tully Hall in New York City and at San Diego’s Rady Shell, Canada’s Glenn Gould Studio, Salzburg’s Grosses Festspielhaus, Dresden’s Semperoper, Copenhagen’s Tivoli Gardens, and Paris’s Palace of Versailles. She has performed at festivals such as the Ravinia, Mostly Mozart, Colorado, and Rockport festivals in the United States; Germany’s Dresden Music festival; Italy’s Festival dei Due Mondi (Spoleto); Switzerland’s Verbier Festival and Snow and Symphony Festival; the Festival de Radio France et Montpellier; and Japan’s Tokyo International Music Festival. Her performances have been featured on National Public Radio, CNN, PBS, 60 Minutes, ABC, From the Top, Radio France, WQXR and WNYC (New York), MDR Kultur and Deutsche Welle (Germany), NHK (Japan), RAI (Italy), and on numerous television and radio stations in Venezuela.

First-prize winner at the Anton G. Rubinstein International Piano Competition in Dresden, Gabriela was also a semifinalist at the 12th Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, where she also received the Jury Discretionary Award. She is a fifth-generation female pianist, who began her piano studies in Caracas with her mother, Alicia Gaggioni. She then attended the Juilliard School, where she earned her Bachelor and Master of Music degrees as a full scholarship student of Yoheved Kaplinsky. Gabriela was a member of Carnegie Hall’s Ensemble Connect and worked on her doctoral studies with Marco Antonio de Almeida in Halle, Germany.

For more information please visit www.gabrielamartinezpiano.com.

Gabriela Martinez is represented by Blu Ocean Arts.